Psychoanalytic therapy aims to explore the hidden emotions, repressed childhood memories, fantasies and thoughts affecting present behavior and relations of the client. The ultimate gain is a sound sense of self, contentment at a higher state of consciousness and self-mastery.

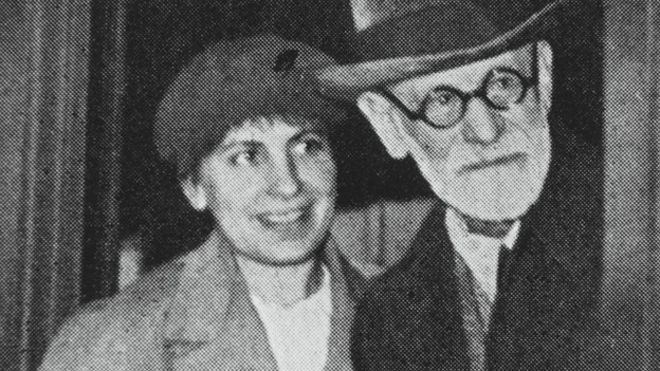

The history of the psychoanalytical practice is not only long but it has been evolving ever since S. Freud’s work in psychoanalysis from 1915s up to present. Moving from the divan (couch) to psychoanalytic therapy wherein the client is relocated to the armchair facing the therapist and further on to the developmental approach founded by S. Freud’s daughter Anna Freud, and finally reaching the present-day research on mother-infant relation and the neurobiology of emotion; the psychoanalytic field continues to render dynamic practices. Extracting the commonalities to draw a general and yet an accurate outline that equally fits all the practices in this field across time is a challenge onto itself.

Throughout my years of education and practice, most of which was under psychoanalytical supervision, I had a chance to experiment few different trajectories and the outline provided here is a synthesis of my experience in the backdrop of the theories of S. and A. Freud, D. Winnicott, E. Erikson, D. Stern, B. Beebe, O. Kernberg and K. Lyons-Ruth with slight variations in the practical methods used with children and adolescents.

This is as simple as it gets!

S. Freud defines the degree of psychological health as the extent that the ego, the seat of reason, can resolve the conflict between ongoing impulses of the id and the sanctions of the superego. Psychopathology resides in misregulation or lack of self-regulation, too much or too little ego defenses employed in daily life, causing maladaptive behavior. Freud’s yardstick of measuring psychopathology is “the symptom which is constructed as a substitute for something else that did not happen” in Strachey, and it implies that there has been a disturbing interruption in the process of development. Analysis aims at uncovering that symptom pushed up by the repressed material stored in the unconscious. This process taking place in the therapeutic relation enables the assessment of the developmental rupture by talking and bringing it to the present and replaying it in the relation between the analyst and the client so that it can be healed and restored in healthier ways. That is why psychoanalytical therapy attributes high importance to transference and countertransference dynamics experienced in the therapeutic relation. They are the medium where affect is exchanged between the client and the therapist and wherein the therapist’s understanding and attunement to the affective states assures the client a secure attachment. The secure attachment style which is the pillar of sound development is also the cornerstone of a successful therapeutic relation. This attachment style invoked in therapy enables the client to know and accept his emotions, and secondly, to create ways of regulating them. Rather than falling back on his maladaptive defenses like denial, the client learns to rebuild them in ways to restore the “self” in the allure of transference and countertransference. As the defenses are reconstructed, the developmental past is also reconstructed, releasing the client from the shadows and traps of the past. Finding a new balance, the ego functions adaptively in service of the coherent and confident “self”.

Duration

The psychoanalytical therapy may take several years, depending on the individual case and choice. It requires minimum 1 session a week; in intensive therapy, the frequency of sessions is 2-3 per week. To end the therapy is a joint decision, tilted more at the discretion of the therapist or the “analyst” according to the traditional school. Jay Greenberg’s view about the ending which resumes “analytical therapy ends when the analyst is enough of an old object” is an intuitive one.

Some techniques used

- The most well-known technique is the talking cure which uses free association: the client says whatever first comes to mind and the therapist says a word. This in-depth talk continues spontaneously, meanwhile the therapist finds and interprets patterns in the client’s responses so they can explore the meaning of these patterns together.

- Dreams reflect the repressed memories and emotions hidden in the unconscious which manifest themselves in the dream either directly or in symbols. They are decoded and interpreted in the sessions to gain access to the inner self.

- Metaphors are rich ways of expression, very useful in communicating and at difficult times.

- Creative expression through playing, use of objects, art, writing and the like are essential tools especially in working with children and adolescents.

The aim of therapy:

- Settling a pattern of self-regulation which would enable the client to balance himself and restore his self-coherence across differing emotional states and life scenarios

- Gain insight and awareness of the unconscious forces that contribute to his current mental-emotional state and behavior

- Understanding the unconscious triggers of recurrent psycho-somatic problems (if any), seeing through the symptom and resolving the knots

- To find or restore the meaning of life, attain a greater sense of fulfilment and navigate oneself with inner clarity

To conclude:

On the continuous nature of self-knowledge and personal growth, the conclusion drawn by A. Freud breeds hope and courage, and honors the human condition:

One may regress or deviate in the development of the self as it happens to many of us at one point or another, yet, given the resilience, when the trauma, disharmony or the rupture is overcome, one can advance once again.

Duygu Bruce

July 13, 2019